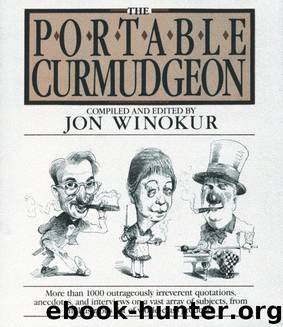

The Portable Curmudgeon by Jon Winokur

Author:Jon Winokur

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: humor, biography, anecdotes, quotations, interviews

Publisher: Jon Winokur

KARL KRAUS

Word and Substance and Empty Chairs

KARL KRAUS, the Viennese dramatist, critic, and satirist, was born in 1874 in a small Bohemian town near Prague to well-to-do Jewish parents. Three years later the family moved to Vienna, where Kraus spent the rest of his life.

He became a writer when a spinal deformity prevented him from realizing his childhood ambition of entering the theater. He contributed acerbic critical essays to Viennese publications and turned down an offer to join the prestigious Viennese daily, Neue Freie Presse, to avoid becoming what he termed a “culture clown.”

He continued to publish polemics against the intellectuals, literati, financiers, politicians, poets, and journalists he deemed responsible for the moral bankruptcy of Europe. His avowed object was no less than the preservation of civilization, which he saw imperiled by the cozy relationship between the Austrian press and intellectuals. He was a consummate rhetorician who equated morality with purity of language. (“Word and substance—that is the only connection I have striven for in my life.”) He assailed the deliberate corruption of language by special interests and railed against what might be termed the artistic-journalistic complex of the time.

He was acquainted with Sigmund Freud and expressed a fondness for him personally but became obsessed with what he considered the chicanery of psychoanalysis. He attacked Freud and his disciples, whom he dubbed “soul doctors” and “psychoanals.” He wrote of Freud’s critique of Michelangelo: “Analysis is the schnorrer’s [beggar’s] need to explain how riches come to be; whatever he doesn’t possess must have been acquired by swindle; the other merely has the fortune; he, fortunately, knows.”

In 1899, he founded his own magazine, Die Fackel (The Torch), with which he relentlessly assaulted the corruption and hypocrisy of European society. In it he denounced prison conditions, price fixing, child labor abuses, and the unequal treatment of women. Initially there were other contributors, including August Strindberg and Heinrich Mann, but from 1911 until his death in 1936, Kraus was its sole contributor. (“I no longer have collaborators. I used to be envious of them. They repel those readers whom I want to lose myself.”)

Die Fackel contained no paid advertisements and professed indifference to its readers; this announcement appeared regularly on its back cover:

It is requested that no books, periodicals, invitations, clippings, leaflets, manuscripts or written information of any sort be sent in. No such material will ever be returned, nor will any letters be answered. Any return postage that may be enclosed will be turned over to charity.

Kraus wrote poetry in which he attempted to objectify his stringent concept of language, and several plays, including Die letzen Tage der Menschheit (The Last Days of Mankind) in 1922, which portrayed the disintegration of European society and prophesied the Second World War. From 1910 until his death, he gave numerous public readings of his own works to enthusiastic audiences all over Europe.

His attitude isolated him from all but a few close friends. He slept days and worked nights and abhorred invasions of his privacy. He recoiled when people accosted him on the street and went to great lengths to avoid human contact.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Wild Words from Wild Women by Stephens Autumn(3157)

776 Stupidest Things Ever Said by Ross Petras(2786)

The Essential Rumi by Coleman Barks(2053)

Lincoln by David Herbert Donald(1994)

Merriam-Webster's Pocket Dictionary by Merriam-Webster(1938)

The Fountainhead by Ayn Rand(1844)

Nobody Knows My Name by James Baldwin(1615)

Memoirs by David Rockefeller(1593)

Torch Song Trilogy by Harvey Fierstein(1577)

Oxymoronica by Dr. Mardy Grothe(1568)

The Yogi Book by Yogi Berra(1529)

The Abolition of Man by C. S. Lewis(1476)

I'm So Full of Happy Today by Martin Andersen & Moira Tuffy(1459)

Worldly Wisdom: Collected Quotations and Aphorisms by Josh Kaufman & Carlos Miceli(1459)

Waiting for the Punch by Marc Maron(1450)

The Wicked Wit of Queen Elizabeth II by Karen Dolby(1429)

Change Your Life!: A Little Book of Big Ideas by Allen Klein(1413)

Totally Scripted by Josh Chetwynd(1375)

That's What She Said by Kimothy Joy(1374)